[I’m writing this on Monday, March 30. Everything in this post might be false in a few days, and conditions might be different in places other than Los Angeles. Keep up to date by checking your local health department website.]

“Don’t stand so close to me.”

— The Police

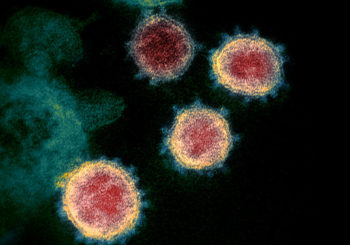

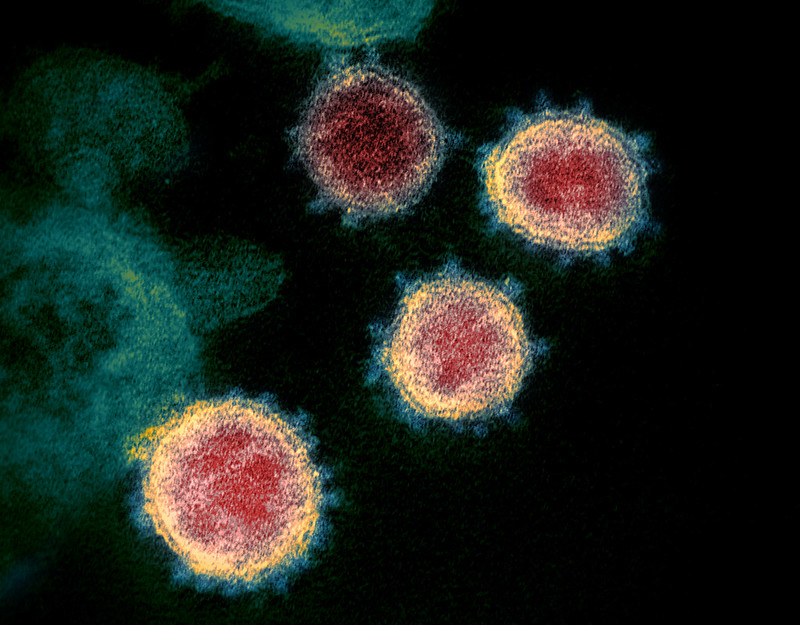

As more and more patients are diagnosed with COVID-19 there’s a lot of discussion about home isolation, home quarantine, and social distancing. In this post I explain which of us should be in each group, and what precautions should be observed by each.

Home Isolation

Who should be in home isolation?

Anyone who has been diagnosed with COVID-19 but does not need to be hospitalized should isolate at home. Being diagnosed with COVID-19 does not necessarily mean having a positive test for COVID-19. (See my post about testing to understand why a test might come back negative even if you have COVID.) Your doctor might decide you have COVID-19 simply based on your symptoms, such as fever and cough. If your symptoms are mild, recovery at home is likely the best course.

What’s involved?

Someone in home isolation should stay home except to get medical care. You should not use public transportation. Getting groceries and medications should be left to someone else. If at all possible, the person in isolation should have his own room and bathroom at home. The isolated person should stay 6 feet away from other housemates. You should not prepare or serve food to others and should not share utensils, towels, or bedding with housemates. You should wear a mask when in the same room as housemates. Visitors to the home should not be allowed. There is much more detailed guidance in the LA County Dept of Health instructions.

You should also talk to your housemates, caregivers, intimate partners and anyone else who was within 6 feet of you for more than 10 minutes. Their exposure to you makes it possible that they will get COVID-19. They should home quarantine even if they have no symptoms. (See next section.)

When should you get medical attention?

If symptoms worsen or if serious symptoms occur such as shortness of breath, vomiting, or changes in metal status, then call your doctor immediately. If a visit to your doctor is planned, call ahead to make sure they understand that a patient with COVID is coming. Wear a mask.

Patients who are at high risk of severe illness – people 65 and older, pregnant women, and patients with chronic medical problems – can deteriorate rapidly. They should have a plan for frequent contact with their doctor (by phone, video or in person).

When does it end?

You should remain in isolation until at least 7 days after your symptoms started and 3 days after recovery. Recovery is the absence of fever without fever-reducing medications and improvement of respiratory symptoms. Then you get to join the rest of us in the social distancing group.

Home Quarantine

Who should be in home quarantine?

Anyone in close contact with someone who has COVID-19 (or presumed to have it) should quarantine at home. It can take 2 to 14 days after infection for symptoms to appear, so even without symptoms quarantine is important to prevent infecting others.

What’s involved?

The restrictions are identical to those for home isolation. The only difference is that there’s no reason to wear a mask since you don’t have any symptoms. It’s especially important to remember that you might be infectious and to avoid people who are at higher risk of serious illness – people who are 65 years and older, pregnant women, and people which chronic medical problems. The LA County Dept of Health has more detailed guidance here.

When should you get medical attention?

If you develop fever, cough, shortness of breath, shivering, body aches, or sore throat, call your doctor. Depending on your symptoms, age and medical problems, your doctor may decide to examine you or just presume you have COVID and ask you to home isolate (the group above).

When does it end?

Quarantine ends 14 days after exposure to the person with COVID-19. If you live with the person with COVID and despite their home isolation are unable to avoid close contact (for example, if you’re her caregiver), your quarantine ends 14 days after her home isolation ends. Then you move to the social distancing group, below.

If you develop symptoms and your doctor decides you are likely to have COVID, you shift to home isolation (above).

Social Distancing

Who should be practicing social distancing?

All of us. If you’re not in one of the above two groups. You should be practicing social distancing.

What’s involved?

Social distancing means staying home and avoiding non-essential trips out of the home. Essential trips out of the home include acquiring groceries and medicines. When out of the home, avoid crowds and stay at least 6 feet away from others whenever possible. Work from home if possible. Cancel routine non-essential healthcare appointments. Avoid public transportation, if possible. You can take walks outside, or bike or hike, as long as you stay 6 feet away from others. The detailed guidance from the Dept of Health is here.

When should you get medical attention?

If you are sick, call your doctor before visiting. She may offer a video or phone appointment.

When does it end?

I have no idea. We’re all waiting for the numbers of new cases in Los Angeles (or in California) to significantly decline day after day, but that hasn’t happened yet. (And such a sustained decline would suggest that we’re about halfway through, not done. We’re only done when there are almost no new daily cases.) Keeping the new cases as few as possible will be essential to making sure that everyone who needs a hospital bed gets one and everyone who needs a ventilator gets one. It would be a great comfort to know now when the social distancing will end, but there’s no way to predict how long it will take to decrease the number of new cases. My son is in Bellevue, King County, a suburb of Seattle, the first American city to have a significant number of COVID-19 cases. He’s been working from home for 3 weeks. The number of new daily cases there are hinting at a downtrend, but nothing is definitive, and there’s no known time yet that his lockdown will be over.

So we do the best we can and we wait. Not having a prespecified finish line makes it much harder. It would be less miserable if we knew now when this would be over, but we don’t. Anyone reading the news out of Italy and out of New York knows what we’re trying to prevent in Los Angeles. If we can’t prevent it, we must try to endure it with minimal loss of life.

My suggestion for all of us in this group is to find ways to support our local hospitals. Donate blood. If you have a stash of surgical face masks (not handmade ones) or N95 respirators, and the realization is dawning on you that ICU doctors and nurses don’t have them, donate them.

I sincerely hope that in a month or so I’ll be able to rewrite this post and describe a fourth group, those known to be immune. People whose immunity could be proven, either because they had a positive test for the coronavirus while they were sick, or because they had a positive antibody test after recovery, would be able to return to work and would be the safest healthcare workers to care for COVID patients. They could resuscitate the economy without spreading disease. As I wrote in my last post, a reliable antibody test is not yet available, but multiple labs are working on it.

Until then, stay inside and stay healthy.

Learn more:

Home Isolation Instructions for People with Coronavirus-2019 (COVID-19) Infection (LA County Dept of Public Health)

Home quarantine guidance for close contacts to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) (LA County Dept of Public Health)

Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Guidance for Social Distancing (Los Angeles County Dept of Public Health)

Blood Donor Services (Cedars Sinai)

Donate Supplies (Cedars Sinai)

My previous posts about the novel coronavirus:

Testing, Testing

Novel Coronavirus FAQ Part 2 – Pandemic Hullabaloo

Coronavirus Frequently Asked Questions

Community Transmission Of Novel Coronavirus In LA County

What You Need To Know About The Novel Coronavirus