Friday, July 3, 2020

I haven’t written for about two months. One reason is that I’ve been busy taking care of my patients. Only three of my patients have contracted COVID, as far as I know. All have recovered. Many others may have had asymptomatic infections. But almost all of my patients have had important COVID-related questions and concerns. Another reason for the blogging pause is that for the last two months I haven’t known what to write, because I didn’t understand what was happening. I still don’t understand what’s happening, but it’s increasingly clear that neither does anyone else, so I thought it was a good time to post an update and propose a shift in strategy.

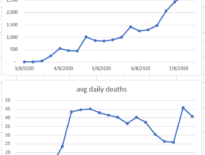

Since the middle of May the number of new daily COVID cases in LA County has been steadily climbing, from 900 new cases daily to just over 2,000 cases daily at the end of June. (COVID statistics are from the Los Angeles County Dept of Public Health. I applied a seven-day average calculated on Sundays.)

I should clarify what a “case” is. A case is a person who tests positive for the novel coronavirus and is reported to the LACDPH. So cases are definitely an undercount of all the COVID infections because they exclude the asymptomatic infections that weren’t tested and they exclude the sick people who recovered at home and weren’t tested. (The number of asymptomatic infections at any given time is an important factor in how quickly COVID can spread and in the risk of being infected in a public place. We don’t have a good estimate of this number.)

During the same time period COVID deaths in LA steadily dropped from an average of 45 daily deaths to about 26 daily deaths. So in about 7 weeks the number of daily cases doubled while the number of daily deaths halved. What’s going on? Is the disease one quarter as deadly as it was 7 weeks ago?

The short answer is that no one knows. Several possible explanations have been explained, and I’ll briefly analyze each.

Deaths lag behind cases by a few weeks. One explanation offered by public health officials is that deaths are a lagging indicator. It takes a few weeks for those who are going to die to die, so case numbers usually rise prior to deaths. That’s true, but deaths don’t lag by seven weeks. If the cases diagnosed in May were going to die at the same rate as those in April, we would have seen an increase in deaths by now.

Increasing case counts are an artifact of increased testing. This theory posits that since more testing is happening, we’re detecting more disease even though the number of actual infections is stable. There is good evidence that this is false. The best evidence against this theory is that the percentage of the tests done that are positive is increasing, suggesting that the number of infected people in the population is going up. The rate of new infections is really increasing.

Hospital care has improved. This is certainly at least part of the story. Recent studies demonstrating the effectiveness of remdesivir and dexamethasone in patients with severe COVID have informed current hospital care. Other best practices like placing patients in the prone position (on their stomachs) have spread, and hospitalists have gotten better at protecting themselves while caring for patients. There’s every reason to believe that this has led to more patients surviving their hospitalization.

The virus has mutated. There isn’t a shred of evidence for this theory, but it deserves some thought. All pathogens (like everything with genes) occasionally mutate. Most mutations are detrimental to the pathogen, but occasionally a random mutation causes a change that helps the pathogen infect more hosts. In general, milder strains of germs spread to more hosts, since a dead host is ineffective at spreading the infection. So over time, evolution tends to favor germs that cause milder disease. There’s no specific reason to believe that the novel coronavirus mutated to a milder strain in May, but one can dream.

The disease is shifting to people who are less vulnerable. Many regions have reported that patients who have been infected recently are younger, on average, and healthier than those infected a few months ago. This trend may simply be due to different isolation behaviors by those at high risk and those at low risk. If high-risk individuals have become ever stricter about social isolation, while those at lower risk have participated in the economic reopening, that would lead to more low-risk individuals being infected and simultaneously to fewer deaths. This is the most intriguing possibility, since it suggests that (again, on average) individuals are making rational decisions balancing their risk of infection and their benefits of social and economic interactions. It suggests that those who have least to lose have returned to work and to play and are being infected without terrible consequences. (The COVID hospitalization census at Cedars-Sinai has been declining or flat until about two weeks ago. There has been a small increase since then.) And those who have most to lose have remained isolated and stayed healthy.

Public health officials in many regions are sounding the alarm about the increasing case counts. In some states businesses that had been opening are reclosing. LA County has resuspended in-restaurant dining, which had only been opened a few weeks ago. Perhaps this is wise. But perhaps a focus on case counts misses the mark. LA County hospital utilization, while increasing, is nowhere near full. We should recall that the point of flattening the curve was to maintain availability of hospital beds, ICU beds, and ventilators. We have done that. Regions like Arizona that are in danger of swamping their bed supply might need to return to stay-at-home orders to keep hospitals open, but while LA County hospitals continue to have open beds, I would like to propose a different pandemic mitigation strategy.

Rather than issue guidance and regulations focused on different establishments (restaurants, retails stores, gyms, etc.), I suggest it would be more effective to issue guidance focused on people of different risk levels. Those at highest risk (people over 65, people with chronic health problems, people who are immunosuppressed) should continue to socially isolate until case counts are negligible or an effective vaccine is available. Those at lowest risk (young healthy people who do not live with high-risk people) should get back to their lives. Yes, their risk isn’t zero. Yes, some of them may end up hospitalized, and even though they would survive, their stay in the ICU might be miserable. But for every one of them in the ICU, hundreds would have very mild disease, and thousands would be able to return to work, to exercise with friends, and to pray with their congregation.

Instead of advice about where we can go, we need advice about who can safely go anywhere and who should stay home. We need public education about which chronic medical problems increase risk so that individuals can make effective decisions for themselves. If death rates stay low and healthcare resources remain available, rising case counts should be seen as evidence of people getting on with their lives, and herd immunity getting closer. This should be met with optimism and with gratitude to the hospitalists whose improving care is making it possible. It is not a reason to retreat to our policies from March.

As we prepare to celebrate our nation’s 244th birthday, I’m disheartened by the many failures we’ve had in managing the pandemic at the federal, state, and local levels. (Why do we still not have enough tests?) Perhaps the diverging case and death counts suggest that a strategy that stratifies patients rather than businesses should be attempted.

Happy Independence Day! Stay well.

Learn more:

COVID-19 page (Los Angeles County Dept of Public Health)

Osterholm update (a weekly podcast about COVID-19 by Dr. Michael Osterholm, epidemiologist and infectious disease specialist)